Optimizing Hard Disk Performance on Linux

| Software version | Kernel 2.6.32+ |

| Operating System | Red Hat 6.3 Debian 7 |

| Website | Kernel Website |

Introduction

Physical hard drives are currently the slowest components in our machines, whether they are mechanical hard drives with platters or even SSDs! But there are ways to optimize their performance according to specific needs. In this article, we'll look at several aspects that should help you understand why bottlenecks can occur, how to avoid them, and solutions for benchmarking.

What causes slowness?

There are several factors that can cause slow disk I/O. If you have mechanical disks, they will be slower than SSDs and have additional constraints:

- The rotation speed of the disks

- The reading speed per second will be better on the outer part of the disks (the part furthest from the center)

- Data that is not aligned on the disk

- Small partitions present on the end of the disk

- The speed of the bus on which the disks are connected

- The seek time, corresponding to the time it takes for the read head to move

Partition alignment

Alignment consists of matching the logical blocks of partitions with the physical blocks to limit read/write operations and thus not hinder performance.

Current SSDs work internally on blocks of 1 or 2 MiB, which is 1,048,576 or 2,097,152 bytes respectively. Considering that a sector stores 512 bytes, it will take 2,048 sectors to store 1,048,576 bytes. While traditionally operating systems started the first partition at the 63rd sector, the latest versions take into account the constraints of SSDs. Thus Parted can automatically align the beginning of partitions on multiples of 2,048 sectors.

To ensure proper alignment of partitions, enter the following command with administrative privileges and verify that the number of sectors at the beginning of each of your partitions is a multiple of 2,048. Here's the command for an MSDOS partition table:

If you have a GPT partition table:

Differences between electromechanical disks and SSDs

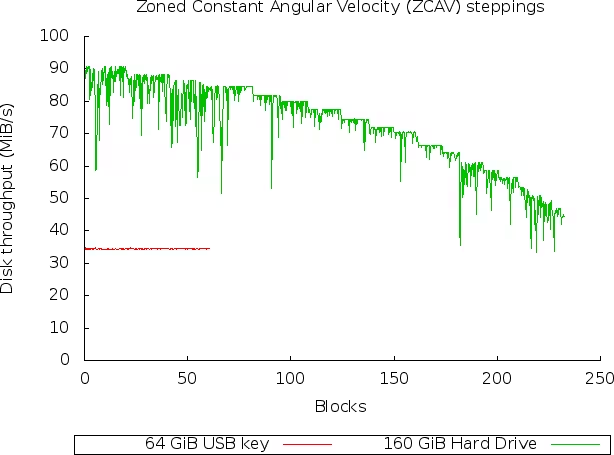

To better understand the difference between the inner part of the disk (closest to the center) and the outer part of the disk (farthest from the center), let me show you a test between a USB drive (linear, equivalent to an SSD) and a hard drive (non-linear). For this we will use a benchmark tool called bonnie++. So we install it:

And we'll launch a capture on both disks with the zcav utility which allows us to test the throughput in raw mode:

The -c option allows you to specify the number of times to read the entire disk.

Then we'll generate a graph of the data with Gnuplot:

As a reminder, I wrote an article on Gnuplot. Here's the result:

We can see very clearly that the hard disk performs very well at the beginning and suffers on the inside. The speed is almost twice as high on the outside as on the inside, and this is explained by the oscillating arm that reads more data over the same period of time on the outside.

Different data buses

There are different types of buses:

- PCI

- PCI-X

- PCIe

- AGP

- ...

Today PCI-X is the fastest. If you have RAID cards, you can check the clock speed to ensure it's running at its maximum to deliver as much throughput as possible. You can find all the necessary information for these buses on Wikipedia. It's important to check:

- Bus size: 32/64 bits

- Clock speed

Here's a small approximate summary (varies with technological advances):

| Object | Latency | Throughput |

|---|---|---|

| 10krpm disk | 3ms | 50MB/s |

| Swap access | 8ms | 50MB/s |

| SSD disk | 0.5ms | 100MB/s |

| Gigabit Ethernet | 1ms | 133MB/s |

| PCI interface | 0.1us | 133MB/s |

| malloc/mmap | 0.1us | |

| fork | 0.1ms | |

| gettimeofday | 1us | |

| context switch | 3us | |

| RAM | 80ns | 8GB/s |

| PCI-Express 16x interface | 10ns | 8GB/s |

| L2 Cache | 5ns | |

| L1 Cache | 1ns | |

| L1 Cache | 0.3ns | 40GB/s |

There are also SCSI type buses. These are a bit special, but you need to be careful not to mix different clock speeds on the same bus, bus sizes, passive/active terminations... You can use the sginfo command to retrieve all the SCSI parameters of your devices:

Caches and transfer rates

Recent disk controllers have built-in caches to speed up read and write access. By default, many manufacturers disable write caching to avoid any data corruption. However, it's possible to configure this cache to greatly accelerate access. Additionally, when these controllers are equipped with a battery, the cards are capable of keeping data for a few hours to a few days. Once the machine is turned on, the card will take care of writing the data to the disk(s).

To calculate the transfer rate of a disk in bytes/second:

For disks using ZCAV, you need to replace sectors per track with the average bytes per track:

I/O requests and caches

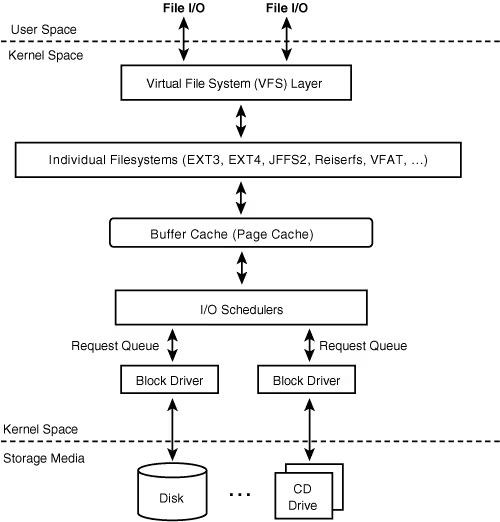

High-level I/O requests such as read/write operations made by the Linux Virtual Filesystem layer must be transformed into block device requests. The kernel then proceeds to queue each block device. Each physical block makes its own queuing request. Queued requests are "Request Descriptors". They describe the data structures that the kernel needs to handle I/O requests. A "request descriptor" can point to an I/O transfer that will in turn point to several disk blocks.

When an I/O request on a device is issued, a special request structure is queued in the "Request Queue" for the device in question. The request structure contains pointers designating the sectors on the disk or the "Buffer Cache (Page Cache)". If the request is:

- to read data, the transfer will be from disk to memory.

- to write data, the transfer will be from memory to disk.

I/O request scheduling is a joint effort. A high-level driver places an I/O request in the request queue. This request is sent to the scheduler which will use an algorithm to process it. To avoid any bottleneck effect, the request will not be processed immediately, but put in blocked or connected mode. Once a certain number of requests is reached, the queue will be disconnected and a low-level driver will handle I/O request transfers to move blocks (disk) and pages (memory).

The unit used for I/O transfer is a page. Each page transferred from the disk corresponds to a page in memory. You can find out the size of cache pages and buffer cache like this:

- Buffers: used for storing filesystem metadata

- Cached: used for caching data files

In User mode, programs don't have direct access to the contents of the buffers. Buffers are managed by the kernel in the "kernel space". The kernel must copy data from these buffers into the user mode space of the process that requested the file/inode represented by cache blocks or memory pages.

Sequential read accesses

Info

Using read-ahead technology only makes sense for applications that read data sequentially! There's no benefit for random accesses.

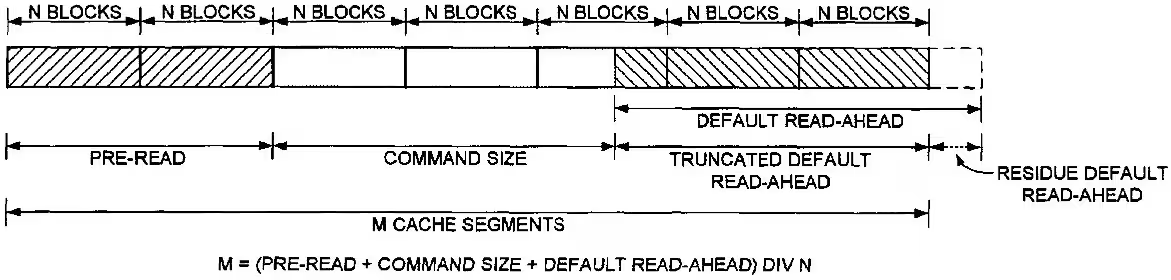

When you make disk accesses, the kernel tries to read data sequentially from the disk. Read-ahead allows reading more blocks than requested to anticipate the demand and store this data in cache. Because when a block is read, it's more than very common to need to read the next block, which is why it can be interesting to tune read-ahead. The advantages of this method are that:

- The kernel is able to respond more quickly to the demand

- The disk controller load is reduced

- Response times are greatly improved

Info

The algorithm is designed to stop itself if it detects too many random accesses so as not to impair performance. So don't be afraid to test this feature.

The read-ahead algorithm is managed by 2 values:

- The current window: it controls the amount of data that the kernel will have to process when it makes I/O accesses.

- The ahead window

When an application requests page access for reading in the buffer cache (which are part of the current window), the I/Os are done on the ahead window! However, when the application has finished reading on the current window, the ahead window becomes the new current window and a new ahead is created. If access to a page is in the current window, the size of the new ahead window will then be increased by 2 pages. If the read-ahead throughput is low, the ahead window size will be gradually reduced.

To know the size of read-aheads in sectors (1 sector = 512 Bytes):

Or in kilobyte:

If you want to benchmark to see the best performance you can achieve with your disks:

However, you should take this information with a pinch of salt because you would need to test it with the application you want to run on this disk to get a truly satisfactory result. So override the value in /sys to change it. Insert it in /etc/rc.local to make it persistent.

Info

The initial read-ahead window is equal to half of the configured one. The configured one corresponds to the maximum size of the read-ahead window!

You can get a report like this:

Schedulers

When the kernel receives multiple I/O requests simultaneously, it must manage them to avoid conflicts. The best solution (from a performance perspective) for disk access is sequential data addressed in logical blocks. In addition, I/O requests are prioritized based on their size. The smaller they are, the higher they are placed in the queue, since the disk will be able to deliver this type of data much more quickly than for large ones.

To avoid bottlenecks, the kernel ensures that all processes get I/Os. It's the scheduler's role to ensure that I/Os at the bottom of the queue are processed and not always postponed. When adding an entry to the queue, the kernel first tries to expand the current queue and insert the new request into it. If this is not possible, the new request will be assigned to another queue that uses an "elevator" algorithm.

To determine which I/O scheduler (elevator algorithm) is in use:

Here are the schedulers you may find:

- deadline: less efficiency, but less response time

- anticipatory: longer wait times, but better efficiency

- noop: the simplest, designed to save CPU

- cfq: tries to be as homogeneous as possible in all aspects

For more official information: http://www.kernel.org/doc/Documentation/block/

To find out the scheduler currently being used:

So it's the algorithm in brackets that's being used. To change the scheduler:

Don't forget to put this line in /etc/rc.local if you want it to persist.

Warning

Don't do the following on a production machine or you risk having severe slowdowns for a few seconds

To write all data in the cache to disk, clear the caches, and ensure the use of the newly chosen algorithm:

cfq

This is the default scheduler on Linux, which stands for: Completely Fair Queuing. This scheduler maintains 64 request queues, the IOs are addressed via the Round Robin algorithm to these queues. The addressed requests are used to minimize the movements of the read heads and thus gain speed.

Possible options are:

- quantum: the total number of requests placed on the dispatch queue per cycle

- queued: the maximum number of requests allowed per queue

To tune the CFQ elevator a bit, we need this package installed to have the ionice command:

ionice allows you to change the read/write priority on a process. Here's an example:

- -p1: activates the request on PID 1000

- -c2: allows specifying the desired class:

- 0: none

- 1: real-time

- 2: best-effort

- 3: idle

- -n7: allows specifying the priority on the chosen command/pid between 0 (most important) and 7 (least important)

deadline

Each scheduler request is assigned an expiration date. When this time has passed, the scheduler moves this request to the disk. To avoid too much solicitation for movements, the deadline scheduler will also handle other requests to a new location on the disk.

It's possible to tune certain parameters such as:

- read_expire: number of milliseconds before each I/O read request expires

- write_expire: number of milliseconds before each I/O write request expires

- fifo_batch: the number of requests to move from the scheduler list to the 'block device' queue

- writes_starved: allows setting the preference on how many times the scheduler must do reads before doing writes. Once the number of reads is reached, the data will be moved to the 'block device' queue and writes will be processed.

- front_merge: a merger (addition) of requests at the bottom of the queue is the normal way requests are processed to be inserted into the queue. After a writes_starved, requests attempt to be added to the beginning of the queue. To disable this feature, set it to 0.

Here are some examples of optimizations I found for DRBD which uses the deadline scheduler:

- Disable front merges:

- Reduce read I/O deadline to 150 milliseconds (the default is 500ms):

- Reduce write I/O deadline to 1500 milliseconds (the default is 3000ms):

anticipatory

In many situations, an application that reads blocks, waits, and resumes will read the blocks that follow the blocks just read. But if the desired data is not in the blocks following the last read, there will be additional latency. To avoid this kind of inconvenience, the anticipatory scheduler will respond to this need by trying to find the blocks that will be requested and put them in cache. The performance gain can then be greatly improved.

Read and write access requests are processed in batches. Each batch corresponds in fact to a grouped response time.

Here are the options:

- read_expire: number of milliseconds before each I/O read request expires

- write_expire: number of milliseconds before each I/O write request expires

- antic_expire: how long to wait for another request before reading the next one

noop

The noop option allows for not using an intelligent algorithm. It serves requests as they come in. It's notably used for host machines in virtualization. Or disks that incorporate TCQ technology to prevent two algorithms from overlapping and causing performance loss instead of gain.

Optimizations for SSDs

You now understand the importance of options and the differences between disks as explained above. For SSDs, there's some tuning to do if you want to have the best performance while optimizing their lifespan.

Alignment

One of the first things to do is to create properly aligned partitions. Here's an example of creating aligned partitions:

- line 1: we create a gpt type label for large partitions (greater than 2Tb)

- line 2: we create a partition that takes the entire disk

- line 3: we indicate that this partition will be of LVM type

TRIM

The TRIM function is disabled by default. You'll also need a kernel at least equal to 2.6.33. In order to use TRIM, you'll need to use one of the filesystems designed for SSDs that support this technology:

- Btrfs

- Ext4

- XFS

- JFS

In your fstab, you'll then need to add the 'discard' option to enable TRIM:

On LVM

It's also possible to enable TRIM on LVM (/etc/lvm/lvm.conf):

noatime

It's possible to disable access times on files. By default, each time you access a file, the access date is recorded on it. If there are many concurrent accesses on a partition, it ends up being felt enormously. That's why you can disable it if this feature is not useful to you. In your fstab, add the noatime option:

It's also possible to use the same functionality for folders:

Scheduler

Simply use deadline. CFQ is not optimal (although it has been revised for SSDs), we don't want to work unnecessarily. Add the elevator option:

SSD Detection

It's possible thanks to UDEV to automatically define the scheduler to use depending on the type of disk (platter or SSD):

Limiting writes

We'll also limit the use of disk writes by putting tmpfs where temporary files are often written. Insert this into your fstab:

References

http://www.mjmwired.net/kernel/Documentation/block/queue-sysfs.txt http://www.ocztechnologyforum.com/forum/showthread.php?85495-Tuning-under-linux-read_ahead_kb-wont-hold-its-value http://static.usenix.org/event/usenix07/tech/full_papers/riska/riska_html/main.html