Memory Addressing and Allocation

| Software version | Kernel 2.6.32+ |

| Operating System | Red Hat 6.3 Debian 7 |

| Website | Kernel Website |

Memory Addressing

For better efficiency, a computer's memory is divided into blocks (chunks) called pages. Page size may vary depending on the processor architecture (32 or 64 bits). RAM is divided into page frames. One page frame can contain one page. When a process wants to access a memory address, a translation from the page to the page frame must be performed. If this information is not already in memory, the kernel must perform a search to manually load this page into the page frame.

When a program needs to use memory, it uses a 'linear address'. On 32-bit systems, only 4GB of RAM can be addressed. It's possible to bypass this limit with a kernel option called PAE^1 allowing up to 64GB of RAM. If you need more, you must switch to a 64-bit system which will allow you to use up to 1TB.

Each process has its own page table. Each PTE (Page Table Entry) contains information about the page frame assigned to a process.

Virtual Address Space

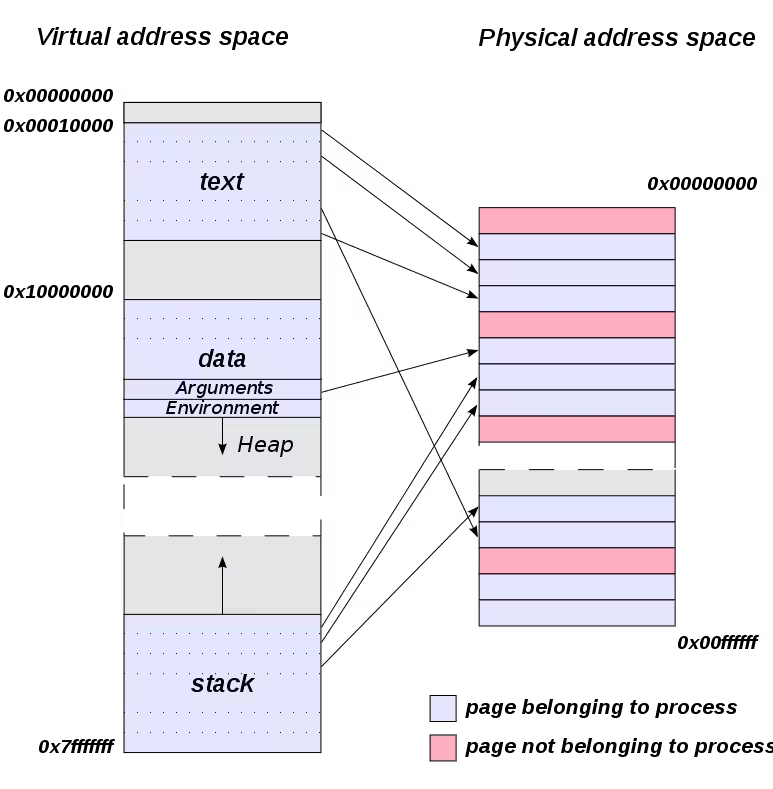

A process's memory in Linux is divided into several sectors:

- text: the code of the executing process, also known as 'text area'

- data: data used by the program. Initialized data will be at the beginning, followed by uninitialized data

- arguments: arguments passed to the program

- environment: environment variables available to the program

- heap: used for dynamic memory allocation (also known as brk)

- stack: used for passing arguments between procedures and dynamic memory

Some processes don't directly manage their memory addressing, leaving two possible solutions:

- The heap and stack can grow toward each other

- No more space available, the process fails to free allocated memory (Memory leaks)

The virtual memory (VMA) of processes can be viewed this way (here PID 1):

Here's another more detailed view (PID 1):

You can also get an even more detailed view of the VMA with pmap (PID 1):

The working sets of a process correspond to a group of pages of a process in memory. A process's working set continuously changes throughout the program's life because memory space allocation varies all the time. For memory page allocation, the kernel constantly ensures which pages are not used in the working set. If pages contain modified data, these pages will be written to disk. If there is no data in the pages, they will be reallocated to other processes with more urgent memory needs.

Memory thrashing occurs when the system spends more time moving pages in and out of a process's working set than simply working with them.

Ulimits

There are limitations on a system. I've already written an article about this[^3]. It's possible to limit memory usage with ulimits. For example, you can define the maximum address space limit.

Physical Address Space

Most processor architectures support different page sizes. For example:

- IA-32: 4KiB, 2MiB and 4MiB.

- IA-64: 4KiB, 8KiB, 64KiB, 256KiB, 1MiB, 4MiB, 16MiB and 256MiB.

The number of TLB entries is fixed but can be expanded by changing the page size.

Virtual Address Mapping

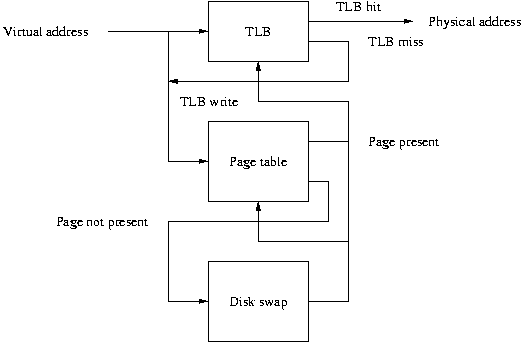

When the kernel needs to access a particular memory space in a page frame, it refers to a virtual address. This is sent to the MMU (Memory Management Unit) on the processor, referencing a process's page table. This virtual address will point to a PTE in the page table. The MMU uses information transmitted by the PTE to locate the physical memory page that the virtual one points to. Each PTE contains a bit to indicate whether the page is currently in memory or has been swapped to disk.

A page table can be likened to a page directory. Paging is done by breaking down the 32 bits of linear addresses that are used as references to memory positions in several places also known as 'page branching structure'. The last 12 bits reference the memory offset in which the memory page is located. The remaining bits are used to specify the page tables. On a 32-bit system, the 20 bits will require a large page table. The linear address will then be divided into 4 segments:

- PGD: The Page Global Directory

- PMD: The Page Middle Directory

- The page table

- The offset

The PGD and PMD can be viewed as page tables that point to other page tables.

Converting linear addresses to physical ones can take some time, which is why processors have small caches also known as TLB (Translation Lookaside Buffer) that store physical addresses recently associated with virtual ones. The size of a TLB cache is the product of the number of TLBs and a processor's page size. For example, for a processor with 64 TLBs and 4KiB pages, the TLB cache will be 256KiB (64*4).

UMA

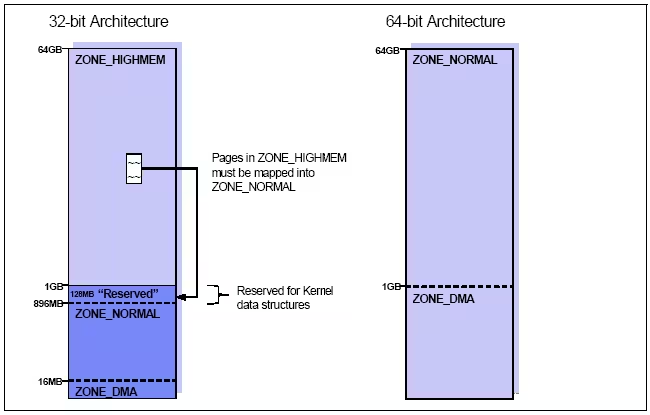

On a 32-bit system, the kernel maps all memory up to 896MiB on the 4GiB linear address space. This allows the kernel to have direct memory access below 896MiB by looking at the linear addressing present in the kernel page tables. The kernel directly maps all memory up to 869KiB except for certain reserved regions:

- 0KiB -> 4KiB: region reserved for BIOS (ZONE_DMA)

- 4KiB -> 640KiB: region mapped in kernel page tables (ZONE_DMA)

- 640KiB -> 1MiB: region reserved for BIOS and IO-type devices (ZONE_DMA)

- 1MiB -> end of kernel data structure: for the kernel and its data structures (ZONE_DMA)

- end of kernel data structure -> 869MiB: region mapped in kernel page tables (ZONE_NORMAL)

- 896MiB -> 1GiB: for the kernel to map its linear addresses reserved in ZONE_HIGHMEM (PAE)^1

On a 64-bit system, however, it's much simpler as you can see!

Memory Allocation

COW (Copy on Write) is a form of demand paging. When a process forks a child, the child process inherits the parent's memory addressing. Instead of wasting CPU cycles copying the parent's address spaces to the child, COW ensures that the parent and child share the same address space. COW is called this way because as soon as the child or parent tries to write to a page, the kernel will create a copy of this page and assign it to the address space of the process trying to write. This technology saves a lot of time.

When a process refers to a virtual address, several things are done before approving access to the requested memory space:

- Verification that the memory address is valid

- Every reference a process makes for a page in memory does not necessarily give immediate access to a page frame. This check is also done

- Each PTE of a process in a page table that contains the bit flag specifying whether the page is present in memory or not is checked

- Access to non-resident pages in memory will generate page faults

- These page faults may be due to programming errors (as in many cases) and will represent memory accesses that have not yet been allocated by a process or already swapped to disk

It's important to know that:

- As soon as a process requests a page that is not present in memory, it will receive a 'page fault' error.

- When virtual memory needs to allocate a new page frame for a process, a 'minor page fault' will occur (with the help of the MMU).

- When the kernel needs to block a process while it is reading from disk, a 'major page fault' will occur

You can see the current page faults (here the PID is 1):

Different Types of RAM

Memory cache consists of static random access (SRAM). SRAM is the fastest memory of all RAMs. The advantage of SRAM (static) over dynamic (DRAM) is that it has shorter cycle times and doesn't need to be refreshed after being read. However, SRAM remains very expensive.

There are also:

- SDRAM (Synchronous Dynamic) uses the processor clock to synchronize IO signals. By coordinating memory accesses, response time is reduced. Basically, a 100Mhz SDRAM equals 10ns access time.

- DDR (Double Data Rate) is a variant of SDRAM and allows reading as soon as it receives rising/falling clock signals.

- RDRAM (Rambus Dynamic) uses narrow buses to go very fast and increase throughput.

- SRAM that we just saw

The RAMs described above range from slowest to fastest.

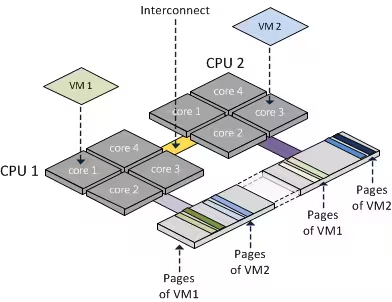

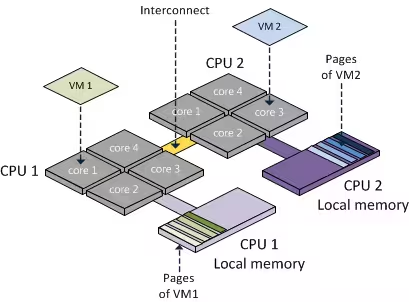

NUMA

NUMA technology increases MMU performance. A 64-bit processor is mandatory to use this technology. You can check if it's present at your kernel level:

Depending on the manufacturers, NUMA technology can be different. This is for example the case between AMD and Intel. For instance, Intel has an MCH controller hub where all memory accesses are routed. This simplifies cache snooping management but can potentially cause bottlenecks for memory accesses. Latency also varies depending on frequency and usage. However, AMD puts different memory ports directly at its CPU level, which surpasses any other SMP technology. With this solution, no bottlenecks, but it complicates cache snooping management which must be managed by all CPUs.

It's possible to have more information about NUMA management on a PID (here 1):

If you want to have finer control of NUMA and decide on processor assignments, you should look at cpuset[^7]. It's widely used for applications that need low latency.

numactl

You can also use the numactl command to force certain CPUs to use specific memory to gain performance. To install it on Red Hat:

On Debian:

To retrieve information from a machine:

and:

Assigning a PID to Specific Processors

You can bind a processor to a CPU:

To allocate memory on the same NUMA node as the processor:

Deactivation

If you wish to disable NUMA, you need to activate "Node Interleaving" in the BIOS. Otherwise at the grub level add (numa=off):

Improving TLB Performance

The kernel allocates and empties its memory using the "Buddy System" algorithm. The purpose of this algorithm is to avoid external memory fragmentation. These fragmentations occur when there are multiple allocations and deallocations of different sizes of page frames. The memory then becomes fragmented into small blocks of free pages interspersed with blocks of allocated memory. When the kernel receives a request for allocating blocks of a page frame of size N, it will first look for available blocks that can contain this size. If none are available, it will try to find N/2 available blocks.

The "Buddy System" algorithm tries to reorder in the most contiguous way possible. You can view available memory like this:

The kernel also supports 'large pages' through the 'hugepages' mechanism (also known as bigpages, largepages, or hugetlbfs). At each context switch encountered, the kernel empties TLB entries for the exiting process.

To determine the size of hugepages:

To choose the size of hugepages, there are 2 solutions:

- With sysctl:

- With grub by adding this parameter:

Warning

Requesting allocation beyond what the machine can provide will result in a kernel panic

For applications to use these spaces, they must use system calls like mmap, shmat, and shmget. In the case of mmap, large pages must be available using the hugetlbfs filesystem:

References

[^3]: Ulimit : Utiliser les limites systèmes

[^7]: Latence des process et kernel timing#cpuset