Better Understanding and Using the C Language Preprocessor

Introduction

In the C language, preprocessing is the preliminary stage before compilation. It’s a powerful mechanism that allows conditional compilation, file inclusion, and macro definition. Although these features appear simple at first glance, they must be used carefully to avoid compilation errors or, worse, program malfunctions. Additionally, the GCC preprocessor has additional features that can be very useful.

A Little-Known Compiler Failure

Thanks to the C macro processor, it’s possible to define and use constants as follows:

#include <stdio.h>

#define CONSTANTE_1 (0x3d+20)

#define CONSTANTE_2 (0x3e+20)

#define CONSTANTE_3 (0x3f+20)

int main(int ac, char *av[])

{

printf("%u\n", CONSTANTE_1);

printf("%u\n", CONSTANTE_2);

printf("%u\n", CONSTANTE_3);

}

If we compile this program, we get an unexpected error:

> gcc main.c

main.c:10:18: error: invalid suffix "+20" for integer constant

The compiler detects an error at line 10, column 18, which is at the CONSTANTE_2 macro. This is a compiler failure that occurs because it thinks it’s dealing with an integer constant denoted by “0x3” with a positive exponent denoted by “e+20”: 0x3 raised to the power of 20. This is not legal notation in C, as exponents are only allowed for floating types. To work around this trap, we need to rewrite CONSTANTE_2 by separating “e” and “+” with a space character:

#define CONSTANTE_2 (0x3e + 20)

This way, compilation and execution can proceed:

> gcc main.c

> ./a.out

81

82

83

Interestingly, this problem exists in the Linux kernel source for PowerPC version. Just look at the file “…/linux-source-2.6.22/include/asm-powerpc/irq.h” to see the following definition that doesn’t compile when used:

#define SIU_INT_PC1 ((uint)0x3e+CPM_IRQ_OFFSET)

It is therefore advised to systematically put a space on both sides of the “+” and “-” operators when defining a macro with the hexadecimal digit “e”.

Macro Termination

It is not recommended to end a macro with a “;” as in the following example:

#define ADD(a, b) a + b;

int main(int ac, char *av[])

{

int r = ac;

if (r)

r = ADD(4, 5);

else

r = ADD(5, 6);

return 0;

}

This leads to a compilation error:

> gcc main.c

main.c: In function "main":

main.c:9: error: expected expression before "else"

Line 9 contains two instructions due to the addition of “;” after the ADD() call. The result of the preprocessor shows this clearly:

> gcc -E main.c

[...]

if (r)

r = 4 + 5;;

else

r = 5 + 6;;

The else instruction is orphaned because the if to which it’s supposed to relate contains more than one instruction that are not grouped by braces: “r = 4 + 5;” and “;”.

Grouping Instructions

When a macro contains multiple instructions such as:

#define ADD(a, b, c) \

printf("%d + %d ", a, b); \

c = a + b; \

printf("= %d\n", c);

You may encounter the compilation error mentioned in section 2 if it is used in an if statement, because the user of the macro might not put braces around the call. Or maybe the macro originally contained only one instruction and was logically used in if statements without being surrounded by braces, but software evolution made it necessary to add additional instructions to it. In the latter case, you risk introducing subtle software malfunctions if, for example, the macro is used in a while instruction without braces:

#include <stdio.h>

#define ADD(a, b, c) \

printf("%d + %d ", a, b); \

c = a + b; \

printf("= %d\n", c);

int main(int ac, char *av[])

{

int i = 0;

int r = 0;

while (av[i++])

ADD(r, 1, r);

return 0;

}

We expect all instructions grouped in ADD() to be executed at each iteration of the loop. Unfortunately, the preprocessor will generate a sequence of instructions without braces, so at each iteration, only the first instruction “printf("%d + %d “, a, b)” will be executed. To avoid such errors, it is advisable to group the instructions in a “do-while” not followed by “;” (rule from section 2), in order to make the multi-instruction macro appear as a single instruction:

#define ADD(a, b, c) do { \

printf("%d + %d ", a, b); \

c = a + b; \

printf("= %d\n", c); \

} while(0)

The compiler will not generate a loop since the iteration condition is always false: while(0). You should not simply use braces, as this would cause the problem from section 2 if the macro was used in an “if-else” due to the “;” that might follow the call in the if body. With the loop not followed by “;”, the user is forced to put a semicolon after the macro call or face a compilation error, but they will have only one instruction: the “do-while” loop.

Parenthesizing Parameters

Consider the following small program that defines and uses a macro performing integer division:

#include <stdio.h>

#define DIV(a, b, c) do { \

printf("%d / %d ", a, b); \

c = a / b; \

printf("= %d\n", c); \

} while(0)

int main(int ac, char *av[])

{

int r = 5;

int v1 = 12;

int v2 = 6;

DIV(v1, v2, r);

DIV(v1 + 6, v2, r);

return 0;

}

When executing, we expect the result 2 for the first division (12 / 6) and the result 3 for the second division ((12 + 6) / 6). But we get the following incorrect result:

> ./a.out

12 / 6 = 2

18 / 6 = 13

As usual, when in doubt with macros, we need to visualize the preprocessor output:

int main(int ac, char *av[])

{

int r = 5;

int v1 = 12;

int v2 = 6;

do { printf("%d / %d ", v1, v2);

r = v1 / v2;

printf("= %d\n", r);

} while(0);

do { printf("%d / %d ", v1 + 6, v2);

r = v1 + 6 / v2;

printf("= %d\n", r);

} while(0);

return 0;

}

We find that we are faced with an operator priority problem in the second call to DIV(). Indeed, in the expression “r = v1 + 6 / v2”, the “/” operator takes precedence over the “+” operator. The compiler therefore generates the equivalent of the mathematical operation “r = v1 + (6 / v2)”. Hence the result 13 when v1 and v2 are 12 and 6 respectively. The solution is to systematically “parenthesize” all occurrences of parameters in a macro:

#define DIV(a, b, c) do { \

printf("%d / %d ", (a), (b)); \

(c) = (a) / (b); \

printf("= %d\n", (c)); \

} while(0)

The second call to DIV() in the previous program now gives the correct result in the preprocessor output:

do { printf("%d / %d ", (v1 + 6), (v2));

(r) = (v1 + 6) / (v2);

printf("= %d\n", (r));

} while(0);

Parenthesizing Expressions

Consider the constant defined as the CONSTANTE macro and used as follows:

#include <stdio.h>

#define BASE 2000

#define CONSTANTE BASE + 2

int main(int ac, char *av[])

{

printf("%d\n", CONSTANTE / 2);

return 0;

}

The expected display is the result of the operation “2002 / 2”, which is 1001. And yet, we get 2001. The preprocessor output shows that the program generates an operator priority problem as seen in section 4:

printf("%d\n", 2000 + 2 / 2);

Generally speaking, if a macro consists of an expression (constant, test, ternary operator…), it is prudent to parenthesize it. Hence the correction of the example:

#define BASE (2000)

#define CONSTANTE (BASE + 2)

Avoiding Expressions as Parameters

We often tend to use a macro as if it were a function, or code evolution may lead to a function becoming a macro for readability or optimization reasons. Here’s an example of a program that defines and uses the IS_BLANK(c) macro that returns true if the parameter is a whitespace character (space or tab):

#include <stdio.h>

#define IS_BLANK(c) ((c) == '\t' || (c) == ' ')

int main(int ac, char *av[])

{

char *p = av[0];

while(*p)

{

if (IS_BLANK(*(p++)))

{

printf("Blank at index %d\n", (p - 1) - av[0]);

}

}

return 0;

}

This program is supposed to display the indices of whitespace characters in its name. However, the displayed index is incorrect or some blanks are not detected:

> gcc main.c -o "name with spaces"

> ./name\ with\ spaces

Blank at index 5

The only detected blank is indicated at index 5, whereas in the string “./name with spaces”, there are blanks at indices 5 and 10. This is because the parameter c is evaluated twice in the IS_BLANK() macro: the first time to be compared to ‘\t’ and the second to be compared to ’ ‘. However, the program passes *(p++) to the macro. This gives in the preprocessor output:

if (((*(p++)) == '\t' || (*(p++)) == ' '))

In other words, the first comparison is with the character pointed to by p, p being then incremented (post-increment), and the second comparison is with the following character. When returning from the macro, p is incremented again. The proper way to write the program is therefore to avoid passing an expression as a parameter to the macro:

#include <stdio.h>

#define IS_BLANK(c) ((c) == '\t' || (c) == ' ')

int main(int ac, char *av[])

{

char *p = av[0];

while(*p)

{

if (IS_BLANK(*p))

{

printf("Blank at index %d\n", p - av[0]);

}

p ++;

}

return 0;

}

It is not always easy to follow this rule, especially if IS_BLANK() was a function and after code evolution, the function became a macro. Indeed, such a modification implies that a complete code review must be done. This is not easy, or even impossible, if the macro is defined in a header file that is already used in many programs around the world.

A GCC-specific extension, not necessarily conforming to ANSI C, offers the opportunity to transform instruction blocks (instructions enclosed by braces) into an expression (cf. [1]). Since it is also possible to declare variables local to a block, the IS_BLANK() macro can be rewritten as follows:

#include <stdio.h>

#define IS_BLANK(c) ({char _c = c; ((_c) == '\t' || (_c) == ' ');})

int main(int ac, char *av[])

{

char *p = av[0];

while(*p)

{

if (IS_BLANK(*(p++)))

{

printf("Blank at index %d\n", (p - 1) - av[0]);

}

}

return 0;

}

The local variable _c was defined inside the macro’s block to store the value of the parameter. Thus, the latter is evaluated only once: at the time of assignment of the local variable.

Variable Number of Arguments

The ISO C99 standard allows defining macros with a variable number of arguments. There are two notations:

#include <stdio.h>

#define DEBUG(fmt, ...) \

fprintf(stderr, fmt „\n", __LINE__, __VA_ARGS__)

#define DEBUG2(fmt, args...) \

fprintf(stderr, fmt „\n", __LINE__, args)

int main(int ac, char *av[])

{

DEBUG("Program name = %s", av[0]);

DEBUG("Message without arguments");

DEBUG2("Program name = %s", av[0]);

DEBUG2("Message without arguments");

return 0;

}

DEBUG() and DEBUG2() are overloads of the fprintf() function to display a formatted error message. The fmt parameter concatenated with character strings is the format passed as the first argument to the display function. The notations VA_ARGS or “args” represent all arguments in variable number with the commas that separate them. The second notation is often preferred to the first one because it allows naming the arguments (for example here with args) instead of using the generic identifier VA_ARGS. The second notation was specific to GCC before macros with variable number of arguments were standardized. On older versions of GCC, it is therefore the only supported notation.

Although very practical, these notations have a major drawback: they do not allow calls without arguments. Here’s the result of compilation followed by the preprocessor output for the previous program:

> gcc main.c

main.c: In function "main":

main.c:12: error: expected expression before ")" token

main.c:15: error: expected expression before ")" token

> gcc -E main.c

[...]

int main(int ac, char *av[])

{

fprintf(stderr, „Program name = %s" „\n", 11, av[0]);

fprintf(stderr, "Message without arguments" "\n", 12, );

fprintf(stderr, "Program name = %s" "\n", 14, av[0]);

fprintf(stderr, "Message without arguments" "\n", 15, );

return 0;

}

The compilation errors come from the comma that precedes the empty list of variable arguments in the second and fourth calls to fprintf(). GCC proposes a very useful extension through the “##” notation to eliminate the comma when the list of arguments that follows it is empty. Hence the following rewrite of the macros:

#define DEBUG(fmt, ...) \

fprintf(stderr, fmt "\n", __LINE__, ## __VA_ARGS__)

#define DEBUG2(fmt, args...) \

fprintf(stderr, fmt „\n", __LINE__, ## args)

Special Macros

There are many macros and notations with a special role for the preprocessor. In this section, only the most useful or at least the most used are mentioned.

GNUC

The GNUC macro is always defined when using the GCC compilation chain. It is therefore recommended for conditional compilation when a program uses GCC-specific extensions, but might be compiled by other compilation chains (see section 9 for an example of use).

LINE, FILE and FUNCTION

The LINE, FILE and FUNCTION macros are respectively replaced by the line number, file name and function name in which they appear. These facilities are generally used for trace and error generation to aid in debugging. To illustrate, here’s a small program that displays its arguments using the DEBUG() macro, whose added value is to print the file name, function name, and line number from which it is called:

#include <stdio.h>

#define DEBUG(fmt, args...) \

fprintf(stderr, „%s(%s)#%d : „ fmt , \

__FILE__, __FUNCTION__, __LINE__, ## args)

int main(int ac, char *av[])

{

int i;

for (i = 0; i < ac; i++)

{

DEBUG("Param %d is : %s\n", i, av[i]);

}

return 0;

}

[...]

> gcc debug.c

> ./a.out param1 param2

debug.c(main)#14 : Param 0 is : ./a.out

debug.c(main)#14 : Param 1 is : param1

debug.c(main)#14 : Param 2 is : param2

Note that FUNCTION is specific to GCC. The C standard came after with the definition func. Although giving an identical result, these two notations had a major difference: the first expands to a constant character string while the other behaved as if, at the beginning of each function, a local array named “func” was defined and initialized with the constant character string containing the function name. So, on one hand, we had a constant that could be concatenated at compile time to other character strings, and on the other hand, we had a variable. But since version 3.4 of the GCC compiler, these two notations are identical and both behave like variables.

The “#” Operator

The “#” notation allows converting a macro parameter to a character string. For example, here is a function that displays a Linux signal number using the CASE_SIG() macro:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <signal.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#define CASE_SIG(s) case (s) : printf("%s\n", "SIGNAL_" #s); break

void signum(int sig)

{

switch(sig)

{

CASE_SIG(SIGINT);

CASE_SIG(SIGTERM);

CASE_SIG(SIGKILL);

CASE_SIG(SIGTRAP);

CASE_SIG(SIGSEGV);

CASE_SIG(SIGCHLD);

[...]

default : printf("???\n");

}

}

int main(int ac, char *av[])

{

if (ac > 1)

{

signum(atoi(av[1]));

}

}

[...]

> gcc signal.c

> ./a.out 5

SIGNAL_SIGTRAP

The “##” Operator

We’ve already seen one form of using “##” in section 7. But there is another form of use where this directive concatenates the lexical elements surrounding it to form a new lexical unit. In the following example, the words CONSTA and NTE are concatenated to form the name CONSTANTE which happens to be a macro defining the constant 233:

#include <stdio.h>

#define CONSTANTE 233

#define CONCAT(a, b) a##b

int main(int ac, char *av[])

{

printf("%d\n", CONCAT(CONSTA, NTE));

}

[...]

> gcc concat.c

> ./a.out

233

How to Eliminate GCC Attributes

Attributes are GCC-specific extensions to increase checks and contribute to the optimization of generated code. Consider the following example which describes the “format” attribute (for more information on GCC attributes, see [4]). funct() calls two functions that perform formatted display in the manner of printf(): the first parameter contains a description of the format of a character string and the variable list of parameters that follow is used to construct the string to display. When calling these display functions, there is a classic programming error: the format requires the address of a character string and a signed integer, but the list of arguments only contains one signed integer.

extern void my_printf1 (const char *fmt, ...);

extern void my_printf2 (const char *fmt, ...)

__attribute__ ((format (printf, 1, 2)));

void funct(void)

{

my_printf1("Display of %s followed by %d\n", 46);

my_printf2("Display of %s followed by %d\n", 46);

}

Compiling this program with the -Wall option will report the programming error (in the form of a “warning”) for line 11, but not for line 9. Indeed, on line 11, we use the my_printf2() function which is defined with the format attribute to indicate that it’s a “printf-like” function that uses a format in argument 1 and that the variable list of arguments starts at the second parameter:

> gcc -c -Wall attribute.c

attribute.c: In function "funct":

attribute.c:11: warning: format "%s" expects type "char *", but argument 2 has type "int"

attribute.c:11: warning: too few arguments for format

While the concept of attributes is practical and powerful, it can cause problems when the compiler used is not GCC. Since the attribute directive is defined with a single parameter (hence the double parenthesis when passing it multiple parameters so that they appear as a single one), it is possible to use conditional compilation to redefine attribute to nothing when the compiler used is not GCC:

#ifndef __GNUC__

#define __attribute__(p) // Nothing

#endif // __GNUC__

In this example, the compilation condition uses the GNUC flag which is defined by default only when GCC is used (see section 9.1).

Conditional Inclusions

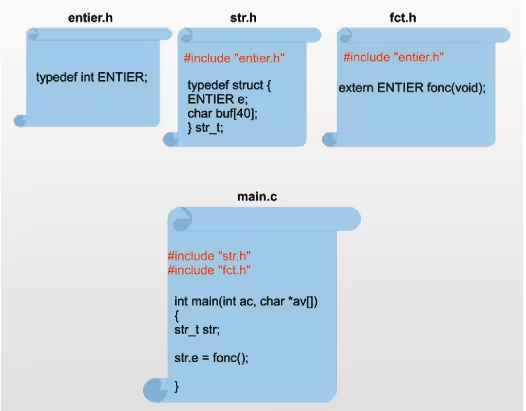

A header file is included in a source file using the “#include” directive. These files most often contain external declarations of variables or functions, type definitions, and macros. A header file can itself include other header files, because a basic rule in C programming is to make a header file independent. In other words, if a header file uses a type, macro, function, or variable, it is recommended that the header file where the corresponding definition is located be included in that file. In the example in figure 1, the main.c file includes the header files str.h and fct.h which respectively define the str_t type and the fonc() function. These last two include the entier.h file for the definition of the ENTIER type.

Compiling main.c gives the following errors:

> gcc -c main.c

In file included from fct.h:1,

from main.c:2:

entier.h:1: error: redefinition of typedef "ENTIER"

entier.h:1: error: previous declaration of "ENTIER" was here

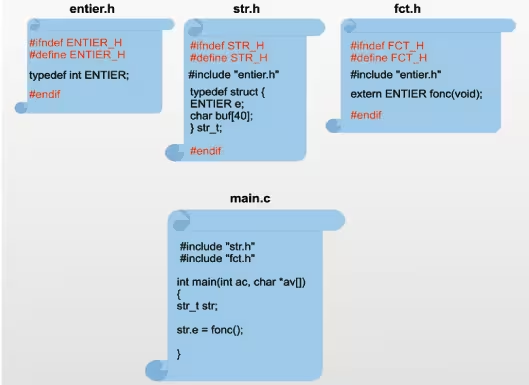

The compiler reports that the ENTIER type is defined twice. The first definition comes from the str.h file and the second from the fct.h file, both of which include the entier.h file. This results in the main.c file including the entier.h file twice. To solve this problem, we can use conditional compilation to include a header file only if a definition specific to it is not already defined. This definition is generally made from the name of the file. To illustrate the point, here’s how the entier.h file is modified to be included only on the condition that ENTIER_H is not already defined:

#ifndef ENTIER_H

#define ENTIER_H

typedef int ENTIER;

#endif // ENTIER_H

This allows compiling main.c, because ENTIER_H is defined by the inclusion of entier.h in str.h and this will therefore prevent the second inclusion of entier.h via fct.h. Generally speaking, it is advisable to apply the principle of conditional inclusion to any header file.

Conclusion

This article has presented numerous rules and tips to make the best use of C preprocessor facilities to help make programs robust, portable, and easy to debug. These are just a subset of the possibilities available. The reader can consult the links and references in this article to go further.

Resources

Last updated 06 Dec 2009, 15:40 +0200.