Memory Caches

| Software version | Kernel 2.6.32+ |

| Operating System | Red Hat 6.3 Debian 7 |

| Website | Kernel Website |

| Last Update | 12/09/2012 |

Page Allocation

Delaying memory allocation when a process requests it is good for performance. Due to reference locality, most programs that request large memory allocations don’t allocate all of it at once. For program memory allocation, it will be done gradually to avoid using more than necessary.

It’s important to understand that there is also priority management based on who makes the request. For virtual memory allocation, for example, when the kernel makes a request, the memory is allocated immediately, whereas a user request will be handled gradually as needed. There are good reasons for these allocation choices. In fact, many RAM-intensive programs have sections that are rarely used. It’s therefore unnecessary to load everything into memory if not everything is used. This helps avoid memory waste. A process whose memory allocation has been delayed during the last minute is referenced as being in demand for pagination.

It’s possible to tune this allocation a bit for applications that typically allocate large blocks and then free the same memory. It also works well for applications that allocate a lot at once and then quit. You need to adjust the sysctl settings:

vm.min_free_kbytes=<value>

This helps reduce pagination request times; memory is only used for what it really needs, and it can put pressure on ZONE_NORMAL1.

Overcommit Management

It’s advantageous for certain applications to let the kernel allocate more memory than the system can offer. This can be done with virtual memory. Using the vm.overcommit_memory parameter in sysctl, it’s possible to ask the kernel to allow an application to make many small allocations:

vm.overcommit_memory=1

To disable this feature:

vm.overcommit_memory=0

It’s also possible to use value 2. This allows overcommitting by an amount equal to the swap size + 50% of physical memory. The 50% can be changed via the ratio parameter:

vm.overcommit_memory=2

vm.overcommit_ratio=50

To estimate the RAM size needed to avoid an OOM (Out Of Memory) condition for the current system workload:

> grep -i Committed_AS /proc/meminfo

Committed_AS: 3458788 kB

Generally, overcommit is useful for scientific applications or those created in Fortran.

Slab Cache

The Slab cache contains pre-allocated memory pools that the kernel will use when it needs to provide space for different types of data structures. When these data structures map only very small pages or are so small that several of them fit into a single page, it’s more efficient for the kernel to allocate pre-allocated memory from the Slab memory space. To get this information:

> cat /proc/slabinfo

slabinfo - version: 2.1

# name <active_objs> <num_objs> <objsize> <objperslab> <pagesperslab> : tunables <limit> <batchcount> <sharedfactor> : slabdata <active_slabs> <num_slabs> <sharedavail>

ext4_groupinfo_1k 31 60 128 30 1 : tunables 120 60 8 : slabdata 2 2 0

jbd2_1k 0 0 1024 4 1 : tunables 54 27 8 : slabdata 0 0 0

ext4_groupinfo_4k 7419 7420 136 28 1 : tunables 120 60 8 : slabdata 265 265 0

ext4_inode_cache 98966 98980 872 4 1 : tunables 54 27 8 : slabdata 24745 24745 0

ext4_xattr 0 0 88 44 1 : tunables 120 60 8 : slabdata 0 0 0

ext4_free_data 1 67 56 67 1 : tunables 120 60 8 : slabdata 1 1 0

ext4_allocation_context 8 28 136 28 1 : tunables 120 60 8 : slabdata 1 1 0

ext4_prealloc_space 31 37 104 37 1 : tunables 120 60 8 : slabdata 1 1 0

ext4_system_zone 0 0 40 92 1 : tunables 120 60 8 : slabdata 0 0 0

ext4_io_end 1 3 1128 3 1 : tunables 24 12 8 : slabdata 1 1 0

ext4_io_page 53 202 16 202 1 : tunables 120 60 8 : slabdata 1 1 0

jbd2_inode 1775 2002 48 77 1 : tunables 120 60 8 : slabdata 26 26 0

jbd2_journal_handle 64 144 24 144 1 : tunables 120 60 8 : slabdata 1 1 0

jbd2_journal_head 590 680 112 34 1 : tunables 120 60 8 : slabdata 20 20 0

jbd2_revoke_table 10 202 16 202 1 : tunables 120 60 8 : slabdata 1 1 0

jbd2_revoke_record 0 0 32 112 1 : tunables 120 60 8 : slabdata 0 0 0

kcopyd_job 0 0 3240 2 2 : tunables 24 12 8 : slabdata 0 0 0

io 0 0 64 59 1 : tunables 120 60 8 : slabdata 0 0 0

dm_uevent 0 0 2608 3 2 : tunables 24 12 8 : slabdata 0 0 0

dm_rq_clone_bio_info 0 0 16 202 1 : tunables 120 60 8 : slabdata 0 0 0

dm_rq_target_io 0 0 408 9 1 : tunables 54 27 8 : slabdata 0 0 0

dm_target_io 856 864 24 144 1 : tunables 120 60 8 : slabdata 6 6 0

dm_io 798 920 40 92 1 : tunables 120 60 8 : slabdata 10 10 0

bio-1 7 20 192 20 1 : tunables 120 60 8 : slabdata 1 1 0

sd_ext_cdb 2 112 32 112 1 : tunables 120 60 8 : slabdata 1 1 0

scsi_sense_cache 60 60 128 30 1 : tunables 120 60 8 : slabdata 2 2 0

scsi_cmd_cache 45 45 256 15 1 : tunables 120 60 8 : slabdata 3 3 0

uhci_urb_priv 3 67 56 67 1 : tunables 120 60 8 : slabdata 1 1 0

sgpool-128 2 2 4096 1 1 : tunables 24 12 8 : slabdata 2 2 0

sgpool-64 2 2 2048 2 1 : tunables 24 12 8 : slabdata 1 1 0

[...]

For a less detailed view:

> vmstat -m

Cache Num Total Size Pages

ext4_groupinfo_1k 31 60 128 30

jbd2_1k 0 0 1024 4

ext4_groupinfo_4k 7419 7420 136 28

ext4_inode_cache 98971 98984 872 4

ext4_xattr 0 0 88 44

ext4_free_data 18 67 56 67

ext4_allocation_context 16 28 136 28

ext4_prealloc_space 37 37 104 37

ext4_system_zone 0 0 40 92

ext4_io_end 2 3 1128 3

ext4_io_page 73 202 16 202

jbd2_inode 1814 2002 48 77

jbd2_journal_handle 9 144 24 144

jbd2_journal_head 609 680 112 34

jbd2_revoke_table 10 202 16 202

jbd2_revoke_record 0 0 32 112

kcopyd_job 0 0 3240 2

io 0 0 64 59

dm_uevent 0 0 2608 3

dm_rq_clone_bio_info 0 0 16 202

dm_rq_target_io 0 0 408 9

dm_target_io 803 864 24 144

dm_io 801 920 40 92

[...]

There’s also a utility that allows you to monitor this Slab cache in real time, you can use the slabtop command:

> slabtop

Active / Total Objects (% used) : 468837 / 561926 (83,4%)

Active / Total Slabs (% used) : 46669 / 46681 (100,0%)

Active / Total Caches (% used) : 108 / 186 (58,1%)

Active / Total Size (% used) : 158581,33K / 169955,34K (93,3%)

Minimum / Average / Maximum Object : 0,02K / 0,30K / 4096,00K

OBJS ACTIVE USE OBJ SIZE SLABS OBJ/SLAB CACHE SIZE NAME

154993 80496 51% 0,10K 4189 37 16756K buffer_head

119300 119300 100% 0,19K 5965 20 23860K dentry

99016 99012 99% 0,85K 24754 4 99016K ext4_inode_cache

28615 24772 86% 0,06K 485 59 1940K size-64

18810 18601 98% 0,17K 855 22 3420K vm_area_struct

15561 12820 82% 0,55K 2223 7 8892K radix_tree_node

15045 14103 93% 0,25K 1003 15 4012K filp

14715 14674 99% 0,14K 545 27 2180K sysfs_dir_cache

14560 11186 76% 0,03K 130 112 520K size-32

12474 11745 94% 0,05K 162 77 648K anon_vma_chain

9420 9218 97% 0,62K 1570 6 6280K shmem_inode_cache

9120 8814 96% 0,50K 1140 8 4560K size-512

[...]

When a process references a file, the kernel creates and associates a ‘dentry object’ for each element in its pathname. For example, for /home/pmavro/.zshrc, the kernel will create 4 ‘dentry objects’:

- /

- home

- pmavro

- zshrc

Each dentry object points to the inode associated with its file. To avoid reading from disk each time these same paths are used, the kernel uses the dentry cache where dentry objects are stored. For the same reasons, the kernel also caches information about inodes, which are therefore contained in the slab.

The ARP Cache

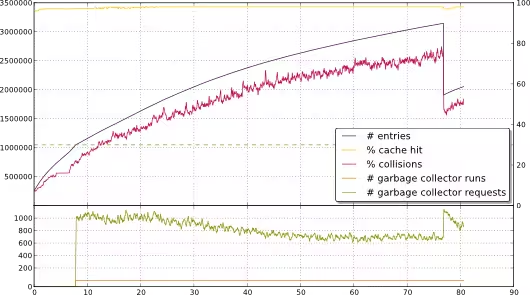

Many network performance problems can be due to the ARP cache being too small. By default, it’s limited to 512 soft entries and 1024 hard entries at the Ulimits level. The soft limit becomes a hard limit after 5 seconds. When this limit is exceeded, the kernel performs garbage collection and scans the cache to purge entries to stay below this limit. This garbage collector can also lead to a complete cache deletion. Let’s say your cache is limited to 1 entry but you’re connecting from 2 remote machines. Each incoming and outgoing packet will cause garbage collection and reinsertion into the ARP cache. There will therefore be a permanent change in the cache. To give you an idea of what can happen on a system:

To see the ARP entries that map hardware addresses to protocol addresses:

> grep -i arp /proc/slabinfo

arp_cache 4 8 448 8 1 : tunables 54 27 8 : slabdata 1 1 0

Too many ARP entries in the cache put pressure on the ZONE_NORMAL. To list ARP entries, there are 2 solutions:

> ip neighbor list

10.101.0.254 dev eth0 lladdr 00:25:45:db:71:57 REACHABLE

or

> cat /proc/net/arp

IP address HW type Flags HW address Mask Device

10.101.0.254 0x1 0x2 00:25:45:db:71:57 * eth0

To clear the ARP cache:

ip neighbor flush dev eth0

You can make some ARP cache adjustments by specifying the soft limit, hard limit, and how often the garbage collector should run (in seconds):

net.ipv4.neigh.default.gc_thresh2=<soft_value>

net.ipv4.neigh.default.gc_thresh3=<hard_value>

net.ipv4.neigh.default.gc_interval=<gc_intrval_value>

There is also another option that allows you to set the minimum time of jiffies in user space to cached entries. There are 100 jiffies in user space in 1 second:

net.ipv4.neigh.default.locktime=<value>

Page Cache

A very large percentage of pagination activity is due to IO. For reading from disk to memory for example, it forms page cache. Here are the cases of page cache verification for IO requests:

- Reading and writing files

- Reading and writing via block device files

- Access to memory-mapped files

- Access that swaps pages

- Reading directories

To see the page cache allocations, just look at the buffer caches:

> grep -i buffer /proc/meminfo

Buffers: 225624 kB

It’s possible to tune the page cache memory size:

vm.lowmem_reserve_ratio=<value>

vm.vfs_cache_presure=<value>

And it’s also possible to tune the arrival rate:

vm.page-cluster=<value>

vm.zone_reclaim_mode=<value>

Anonymous Pages

In Linux, only certain types of pages are swapped. There’s no need to swap text-type programs because they already exist on disk. Also, for memory that has been used to store files with modified content, the kernel will take the lead and write the data to the file it belongs to rather than to swap. Only pages that have no association with a file are written to swap.

The swap cache is used to keep track of pages that have previously been taken out of swap and haven’t been re-swapped since. If the kernel swaps threads that need to swap a page later, if it finds an entry for this page in the swap cache, it’s possible to swap without having to write to disk.

The statm file for each PID allows you to see anonymous pages (here PID 1):

> cat /proc/1/statm

2659 209 174 9 0 81 0

- 2659: total program size

- 209: resident set size (RSS)

- 174: shared pages (from shared mappings)

- 9: text (code)

- 81: data + stack

This therefore contains the RSS and shared memory used by a process. But actually the RSS provided by the kernel consists of anonymous and shared pages, hence:

Anonymous Pages = RSS - Shared

SysV IPC

Another thing that consumes memory is the memory for IPC communications.

Semaphores allow 2 or more processes to coordinate access to shared resources.

Message Queues allow processes to coordinate for message exchanges. Shared memory regions allow processes to communicate by reading and writing to the same memory regions.

A process may wish to use one of these mechanisms but must make appropriate system calls to access the desired resources.

It’s possible to put limits on these IPCs on SYSV systems. To see the current list:

> ipcs -l

------ Shared Memory Limits --------

max number of segments = 4096

max seg size (kbytes) = 32768

max total shared memory (kbytes) = 8388608

min seg size (bytes) = 1

------ Semaphore Limits --------

max number of arrays = 128

max semaphores per array = 250

max semaphores system wide = 32000

max ops per semop call = 32

semaphore max value = 32767

------ Messages Limits --------

max queues system wide = 7599

max size of message (bytes) = 8192

default max size of queue (bytes) = 16384

Using /dev/shm can be a solution to significantly reduce the service time of certain applications. However, be careful when using this system as temporary storage space because it’s in memory. There’s also an ‘ipcrm’ command to force the deletion of shared memory segments. But generally, you’ll never need to use this command.

It’s possible to tune these values (present in /proc/sys/kernel) via sysctl:

> cat sem

250 32000 32 128

- 250: maximum number of semaphores per semaphore array

- 32000: maximum number of semaphores allocated on the system side

- 32: maximum number of operations allocated per semaphore system call

- 128: number of semaphore arrays

If you want to modify them:

kernel.sem = 250 256000 32 1024

There are other interesting parameters (with their default values):

# Maximum number of bytes in a message queue

kernel.msgmnb=16384

# Maximum number of message identifiers in the queue

kernel.msgmni=16

# Maximum size of a message that can be passed to a process (this memory cannot be swapped)

kernel.msgmax=8192

# Maximum number of shared memory segments on the system side

kernel.shmmni=4096

# Maximum size of shared memory segments that can be created. A 32-bit system supports up to 4G - 1 maximum

kernel.shmmax=33554432

# Total amount of shared memory in pages that can be used at once on the system side. This value must be at least kernel.shmmax/PAGE_SIZE (4KiB on 32-bit)

kernel.shmall=2097152

For more information, see the man page for proc(5).

Getting Memory Information

There are several solutions for retrieving memory sizes. The most well-known is the free command:

> free -ltm

total used free shared buffers cached

Mem: 3801 3520 281 0 224 1822

Low: 3801 3520 281

High: 0 0 0

-/+ buffers/cache: 1473 2328

Swap: 3811 4 3807

Total: 7613 3524 4089

You can also get information from dmesg. As we’ve seen above, it’s possible to get the total size of virtual space from meminfo:

> grep -i vmalloc /proc/meminfo

VmallocTotal: 34359738367 kB

VmallocUsed: 560128 kB

VmallocChunk: 34359113168 kB

To see the largest free chunk size:

> grep -i chunk /proc/meminfo

VmallocChunk: 34359113168 kB

For page tables:

> vmstat -s

3892968 K total memory

3585172 K used memory

1991172 K active memory

1348148 K inactive memory

307796 K free memory

230100 K buffer memory

1822744 K swap cache

3903484 K total swap

4140 K used swap

3899344 K free swap

397323 non-nice user cpu ticks

6518 nice user cpu ticks

102540 system cpu ticks

5898943 idle cpu ticks

146534 IO-wait cpu ticks

1 IRQ cpu ticks

1476 softirq cpu ticks

0 stolen cpu ticks

24899538 pages paged in

24575197 pages paged out

43 pages swapped in

1061 pages swapped out

38389133 interrupts

74156999 CPU context switches

1347436271 boot time

171650 forks

For IO allocations, there’s iomem:

> cat /proc/iomem

00000000-0000ffff : reserved

00010000-0009fbff : System RAM

0009fc00-0009ffff : RAM buffer

000a0000-000bffff : PCI Bus 0000:00

000c0000-000effff : PCI Bus 0000:00

000c0000-000c7fff : Video ROM

000ce800-000cffff : Adapter ROM

000f0000-000fffff : PCI Bus 0000:00

000f0000-000fffff : reserved

000f0000-000fffff : System ROM

00100000-cd9ffbff : System RAM

01000000-01354585 : Kernel code

01354586-0169367f : Kernel data

01727000-01805fff : Kernel bss

cd9ffc00-cda53bff : ACPI Non-volatile Storage

cda53c00-cda55bff : ACPI Tables

cda55c00-dfffffff : reserved

cdb00000-dfffffff : PCI Bus 0000:00

d0000000-dfffffff : 0000:00:02.0

e0000000-efffffff : PCI MMCONFIG 0000 [bus 00-ff]

e0000000-efffffff : reserved

f0000000-fed003ff : reserved

f0000000-fec00000 : PCI Bus 0000:00

f0000000-f01fffff : PCI Bus 0000:02

[...]

References

Last updated 12 Sep 2012, 16:58 CEST.